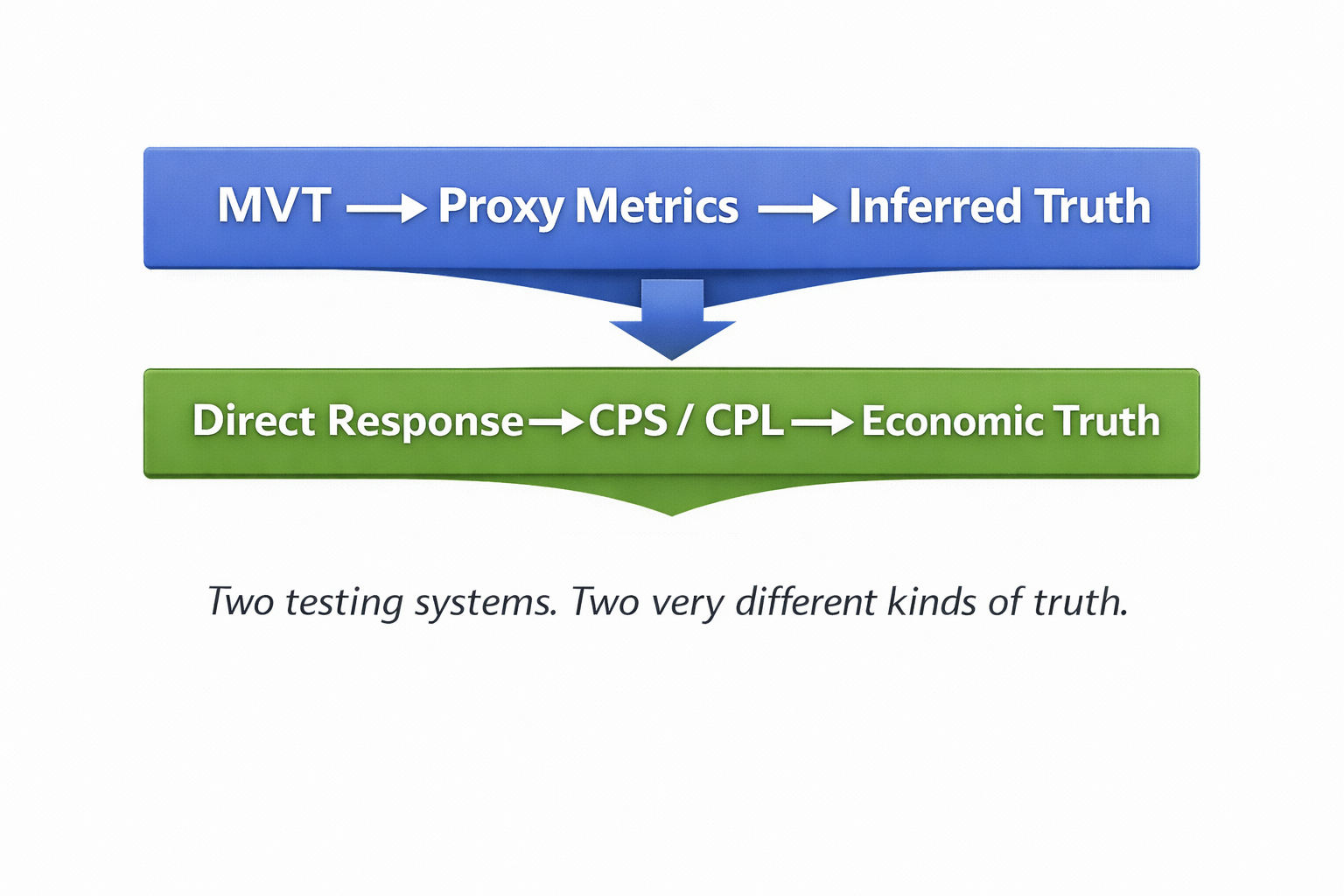

Multivariate Testing Creates Inferred Truth. A/B Control Testing Reveals Economic Truth

Direct mail multivariate testing is very good at identifying which combinations of copy, headlines, guarantees, or offers perform better inside a controlled testing system. It works by changing one element at a time across multiple packages and measuring small differences in response.

For example, one test package might use a different headline. Another might adjust the guarantee language. Another might modify a paragraph of copy. Each of these variations is mailed, and response is recorded. Over time, the system identifies marginal improvements and combines them into what is assumed to be the next “best” package.

What often goes unnoticed is how that final package is actually created.

It is not tested as a complete package against a true control. Instead, it is assembled from a series of small lifts that occurred in separate tests. The logic is that if each individual change improved response slightly, then the combined version should perform better overall.

But that conclusion is inferred, not verified.

The final package is produced through statistical modeling and probability rather than through direct competition against the original control package. It becomes the next version to rotate into the multivariate system, where it is again evaluated by proxy signals instead of confirmed economic outcomes such as CPS and CPL.

The system becomes very good at optimizing within itself.

It becomes far weaker at answering whether what is being optimized actually sustains the business.

That difference is not academic. It determines whether a testing system produces reports that look successful or decisions that actually sustain revenue and profit over time.

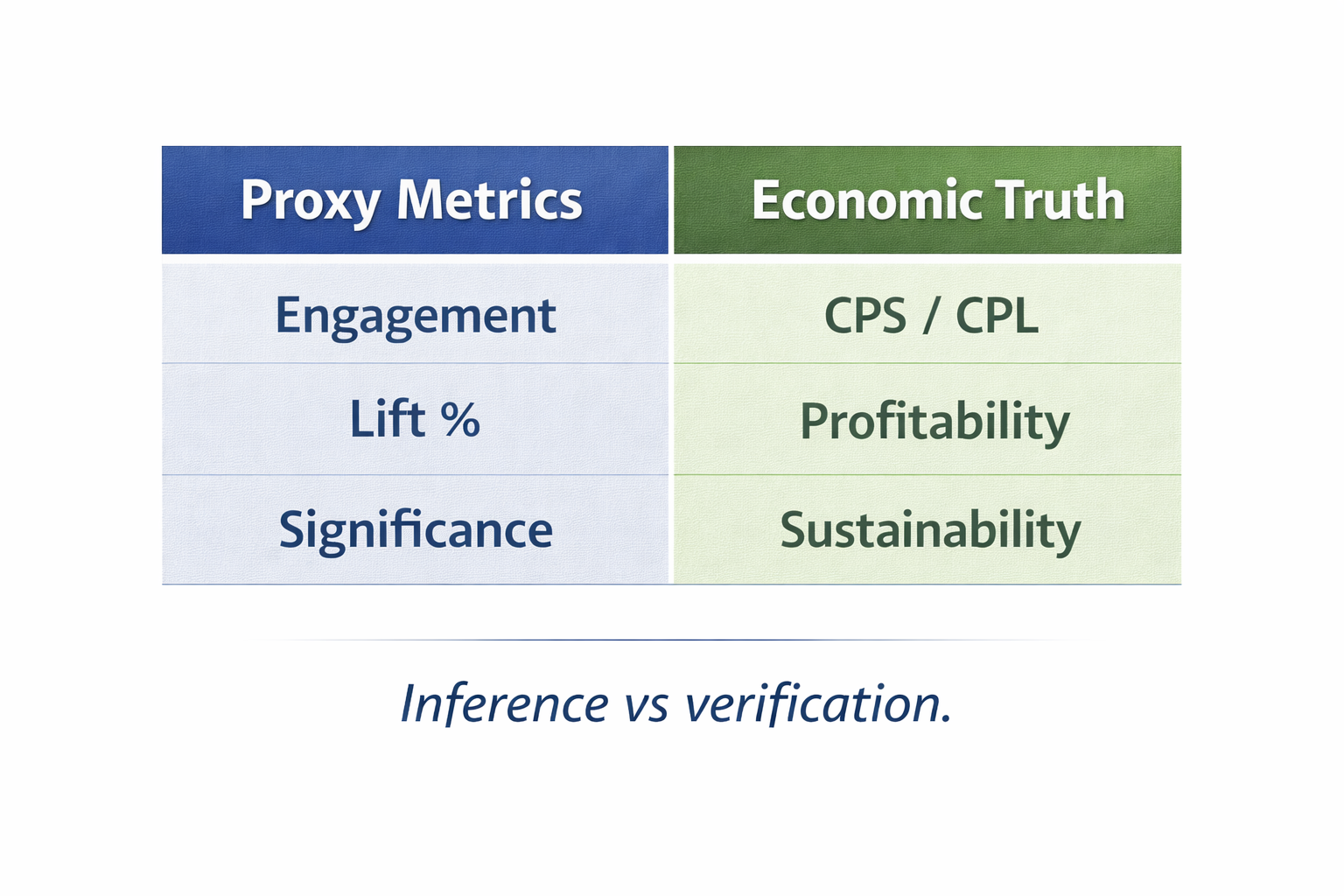

Figure 2. Proxy Metrics vs Economic Truth

Multivariate testing produces what can be called inferred truth. It tells you what is more likely to perform better based on patterns observed inside a modeling environment. It offers confidence that changes are improving results, even though those improvements are never directly validated as a complete package against a true benchmark.

Best-of-breed direct response does not imply performance. It verifies it.

A true direct response test is conducted using A/B splits against a control. One package is designated as the control. A challenger package is created. Both are mailed to comparable audiences simultaneously. The results are measured using cost per lead (CPL) and cost per sale (CPS). There is no modeling layer between the decision and the outcome.

The challenger either beats the control to become the new control based on the Cost Per Sale (CPS) or the Cost Per Lead (CPL), or it does not.

There is no assumption. There is no probability. There is only consequence.

This is what makes direct response testing a system of economic truth rather than proxy truth. It forces each new idea to stand on its own based on results from the test scenario. It does not allow combinations of marginal improvements to be mistaken for validated success.

When cost per lead or cost per sale improves in a control-based test, the business outcome is known rather than estimated.

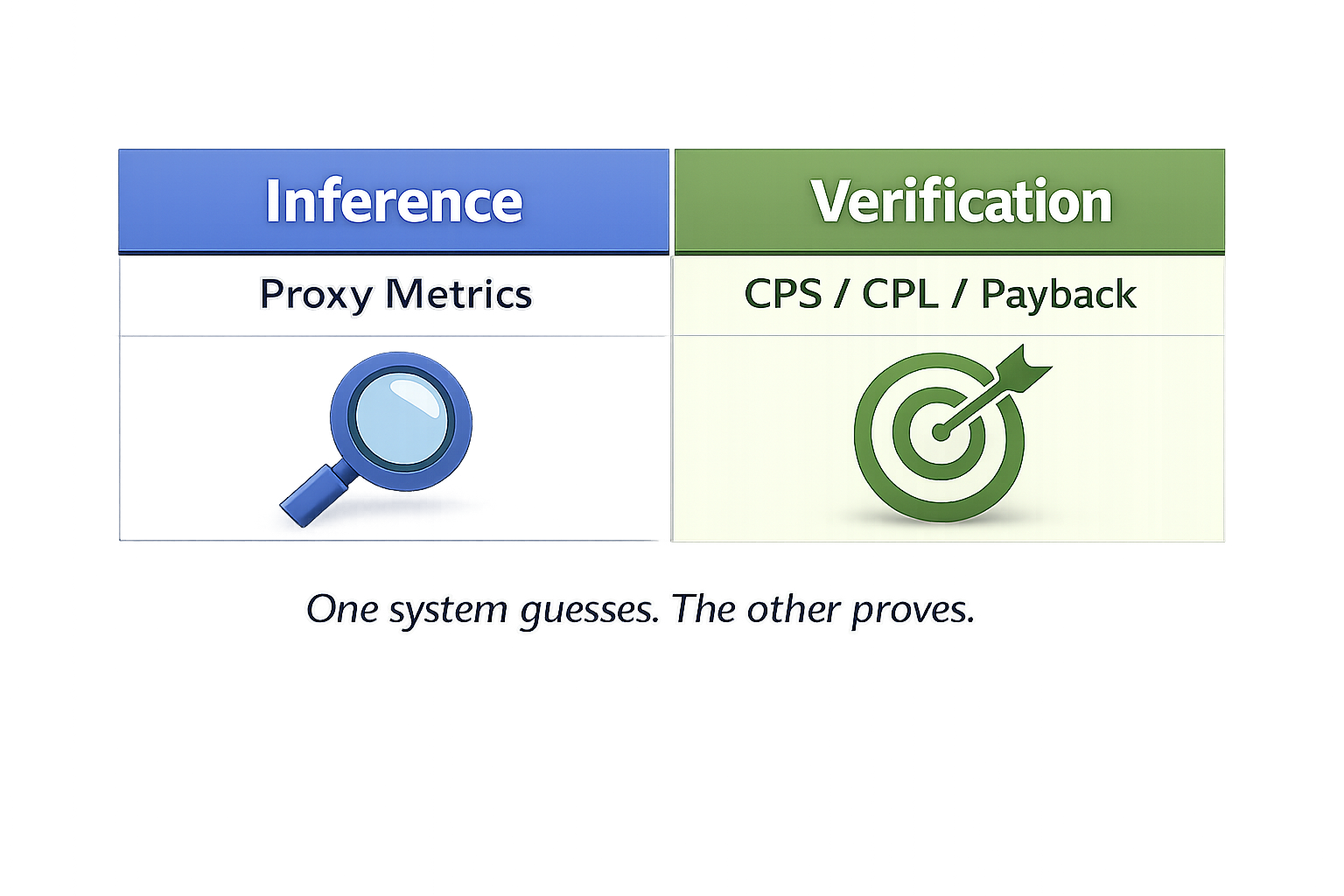

Figure 3. Inference vs Verification

There are only two kinds of truth in marketing: inference and verification.

Inference is built from proxy metrics, correlations, and probabilities. Verification is built from CPS, CPL, payback, and profit. Multivariate testing functions as an inference engine. Direct response testing should function as a verification engine.

Figure 3 illustrates this contrast clearly. One system estimates performance. The other proves it.

This difference reshapes how strategy should be tested.

Optimization assumes the strategy is already correct. Diagnosis asks whether the strategy itself is flawed. That is why direct response is not merely a channel. It is a diagnostic environment in which business strategy is exposed and measured.

Most teams are not misled because they are careless. They are misled because modern systems reward speed, activity, and optimization. Dashboards make progress look visible. Iteration feels like learning.

But multivariate testing answers only one narrow question: which version wins inside the model?

Direct response asks a harder question: what does the test actually reveal about the business decision? Is the result strong enough to justify a rollout measured in millions of direct mail packages?

Historically, multivariate testing increased because digital systems enabled rapid experimentation and computing made statistics more affordable. These were logical and useful developments. But over time, measurement began to replace judgment, and testing began to replace thinking.

Teams stopped asking which direct mail package wins financially in the marketplace and began asking only which version performs better inside the testing system. In the process, response was no longer evaluated primarily through CPS and CPL KPIs.

Over time, the tools themselves began to shape the questions teams were willing to ask. As optimization systems became more sophisticated, strategy was gradually redefined around what those systems could measure easily. Rather than assessing whether a direct mail program was economically sound, teams focused on which version performed better in the test environment. In this way, the questions narrowed, and the strategy followed them. What began as a method for learning became a method for reinforcing existing assumptions.

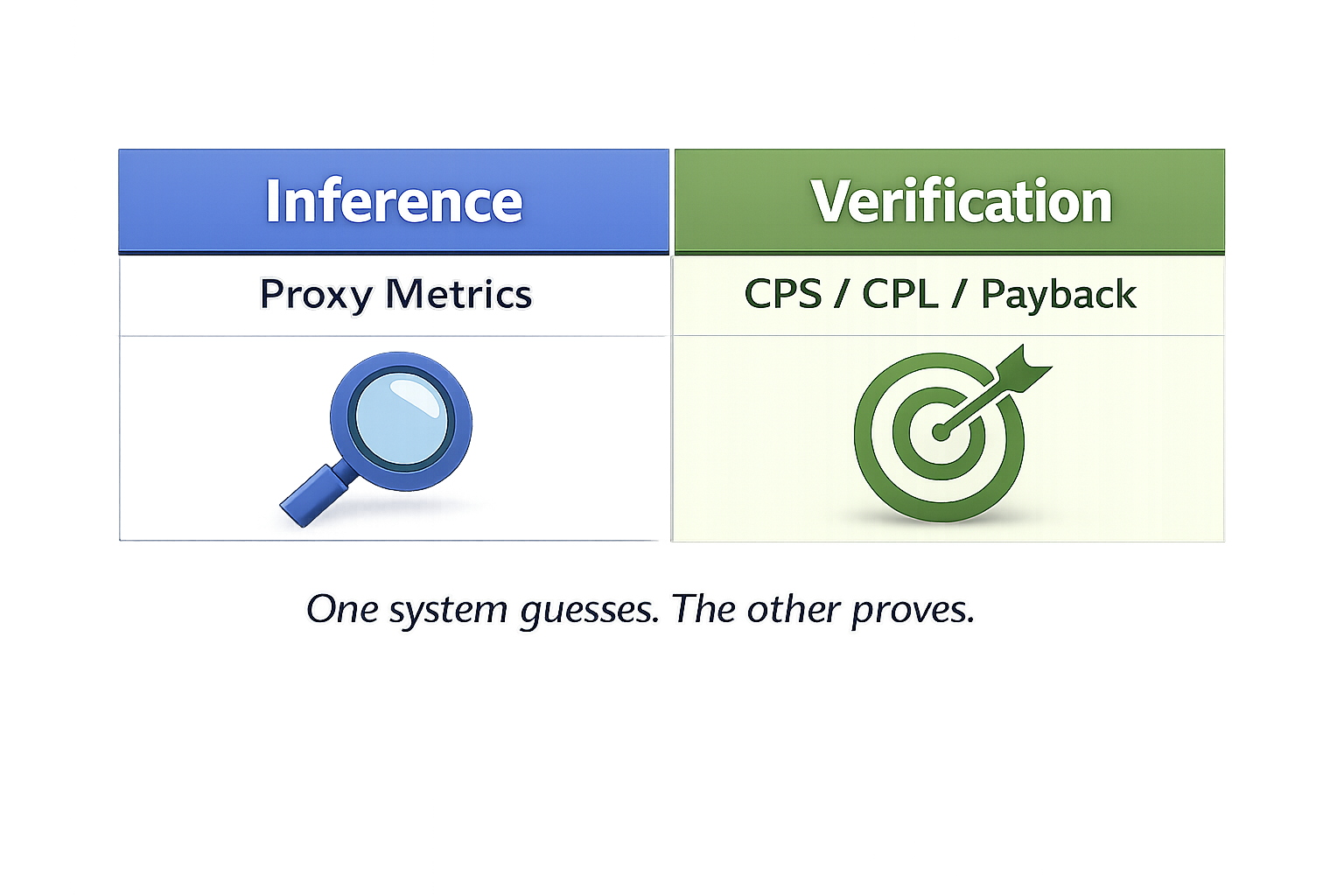

Figure 4. Core Principle

Figure 4 illustrates the core principle at stake: tools do not determine what matters. Financial results do. When tools begin to define the questions, strategy gradually becomes an output of models rather than a disciplined effort to identify the most profitable direct mail possible in both the short and long term.

Multivariate testing optimizes performance inside a closed system of inference. Classic direct response testing, by contrast, requires learning that responds to verifiable economic outcomes measured through cost per lead and cost per sale. One system improves what already exists. The other forces new ideas to prove themselves in the marketplace.

This places responsibility back where it belongs—with leadership. Leaders must decide which kind of truth will govern their decisions before deciding which tools to trust. Testing should serve strategy, not replace it. Models can refine execution, but they cannot define direction in the way classic direct response testing does.

Strategy must come first. The tools should follow.